There’s a familiar story people like to tell about Gen Z: that they’re tuning out, logging off, opting out. But if you actually listen, if you watch how they move through the world, that’s not what’s happening.

What emerges, through data and conversation, is a generation trying, earnestly, to meet deeply human needs: to feel seen, to be part of something, to participate in shaping the world around them. But they’re doing it with tools that were never designed for that purpose.

This isn’t just a story about digital life. It’s a story about loneliness, disconnection, and disappointment.

IRL is Disappearing

Before we talk about digital life, we should sit with what’s been lost. Sociologists call them “third places”: not home, not work, but the spots where you linger, laugh, learn something unexpected. When we ask people where they feel like they truly belong, it’s rarely their job or couch. They say places like: the rec league gym, the library nook, or the coffee shop.

But, for young people especially, those places are disappearing or getting priced out of reach.

“Libraries and museums are getting defunded.” – 27, Female, Independent, Marion, IN

“There's a couple libraries in public spaces where you can get stuff done, but it isn't very robust.” – 22, Male, Democrat, Sacramento, CA

“I feel like there is an ample amount of resources available to adequately fit all facets of life, but certain aspects such as groceries and gym memberships can be expensive.” – 24, Male, Republican, Dekalb, GA

Third places used to be funded by towns, sustained by communities, or simply free. Now they’re $7 lattes, $35 drop-in yoga classes, or a $500+ re-sold concert ticket. If you’re one of the 61% of young men or 70% of young women who say they’re financially struggling or just getting by, these remaining third places aren’t actually accessible.

Online Communities

So much of what grounded community has disappeared from the physical world, but the need to connect didn’t vanish with it. As such, many young people have gone searching for it online. And the language they use to describe those digital spaces where they feel a sense of belonging tells you a lot about what they’re hoping to find and what is still missing:

For Gen Z (ages 18–29), it’s all about “gaming,” and niche affinity spaces like “Discord” and “Twitch”. These are spaces where identity (think “LGBTQ,” or “Swifties”) and shared interests collide. Millennials and the younger in Gen X (30–54) still orbit “community,” but now it’s tethered to “media,” “networks,” and “Reddit”—a mix of utility and curiosity. And then there’s the 55+ crowd: less Twitch, more touch. Their sense of belonging clusters around “Facebook,” “Linkedin,” and “friends” which are spaces that mimic in-person social life and preserve real-world ties.

It’s worth noting that the digital communities cited by older generations were originally built to extend real-world relationships: college friends, co-workers, cousins across the country. The design assumed physical proximity and layered on digital convenience. But for younger people, many of the spaces they frequent are online-first, which changes the emotional texture of connection.

We’ve Built Platforms, Not Places

So it turns out we have built platforms but not places.

Look closely at where young adults say they find belonging, and you’ll see a clear pattern: the more grounded the community is in real-world relationships and shared purpose, the higher their life satisfaction.

Now compare that to the digital realm. Among those who find belonging online or through social media, just 59% say they’re satisfied with life. And there is a 10-point gender gap, where young women are more dissatisfied than young men. But across the board, for young people, these numbers are lower than any of the in-person categories and nearly identical to the 58% who say they don’t belong to any group at all.

Why might this be? If digital life offers constant access to other people, why doesn’t it translate into deeper satisfaction? Hearing it from young people themselves offers clues:

“I think there's a lot of hatred online and negative stories making it hard to keep your head up.” – 18, Male, Democrat, Pinellas, FL

“Technology and social media have wreaked havoc on our communities, causing an inexplicable decrease in people's willingness and ability to connect with others outside of social media.” – 27, Female, Democrat, Hennepin, MN

“Social media has made everyone more and less connected than ever before.” – 27, Male, Republican, Hartford, CT

So while tech companies sell us the idea that their platforms are community, young people are telling a different story: one where the edges of digital life are fraying, and the warmth of real community—be it a team, a congregation, a volunteer crew, or a work pod—is still where people feel most whole.

Digital Life is also Civic Life

But connection isn’t the only thing young people are trying to find online. Increasingly, it’s also where they go to understand how the world works and how they might participate in it. In the absence of strong civic infrastructure, and with traditional institutions feeling distant or distrusted, digital platforms have become the default gateway to news, politics, and public life.

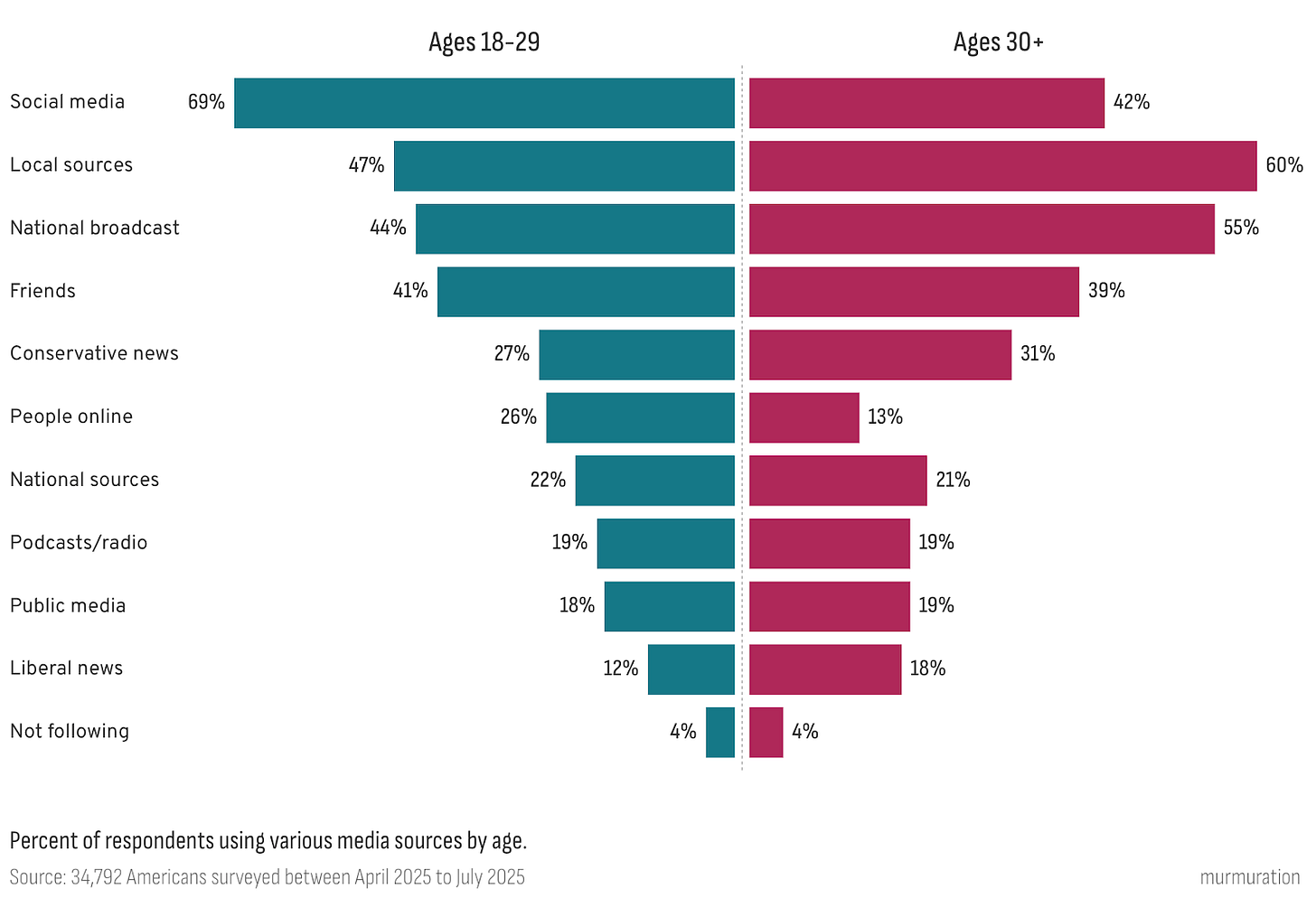

This isn’t just a generational divide in which platforms people use. It’s about the networks of trust and habit they’ve built around information. For older folks, it’s still a blend of place-based reporting and nationally trusted institutions. For young people, the filter is social: friends, influencers, and creators. Their open-ended responses show just how deeply digital life has embedded itself into their broader awareness:

“Social media is my go to source for learning what’s happening in the world. I use it everyday to stay informed or to keep up with news or other topics that interest me.” – 24, Male, Independent, Aiken, SC

“As much as I hate to admit it, I normally end up on Instagram and receive news from there.” – 24, Female, Democrat, Los Angeles, CA

“Social media like Tik Tok. It sounds dumb, but I have a better understanding of what goes on because I get to hear various peoples opinions.” – 18, Female, Independent, Hidalgo, TX

Here’s the twist: it’s not that young people don’t want to be informed. They clearly do. What’s striking is how often they describe social media as their default. Not because it’s ideal. Not because they trust it. Not because they want to use it. But because it’s what is available, familiar, and fast.

Final Thoughts

If there’s a thread running through it all, it’s this: Gen Z isn’t lost. But they are searching…for trust, for connection, for meaning.

And they are telling us what they need. Not just content moderation or mental health apps or voting stickers. But actual infrastructure—digital and physical—that allows them to feel seen, safe, and supported.

So the next time someone tells you young people are opting out, maybe instead try asking a question:

What have we built for them that’s worth opting into?

If young people are building new cultures online, how do the rest of us learn the language?

Are we confusing visibility with connection, and performance with participation?

Questions like these were at the heart of the Semafor panel I joined last week. From our conversation, what stayed with me most was not a specific statistic or policy proposal. It was the growing recognition that young people are not disengaged or apathetic—they are navigating systems that were not designed with humans in mind.

It turns out you can’t build community through code alone.